Deborah Tyler-Bennett is a poet and fiction writer with eight volumes of poems and three volumes of short linked stories to her credit. She is currently working on her first novel, Livin' in a Great Big Way. Her new volume, Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday, will be out from King's England in 2019.

Her poems have also been featured in anthologies that include Bollocks to Brexit: an Anthology of Poems and Short Fiction (CivicLeicester, 2019), Leicester 2084 AD: New Poems about The City (CivicLeicester, 2018) and Welcome to Leicester (Dahlia Publishing, 2016).

In an earlier interview, Deborah talked about her concerns as a writer, and some of the influences she draws on.

In this new interview, Deborah talks about her latest book, Mr Bowlly Regrets, and about poetry and politics:

Do you write every day?

I do write everyday: on trains; in cafés; in bars; at home; in other settings. I try and give myself a timetable between teaching Adult Ed creative writing, workshops, and performances, and the writing itself. I think the important thing is to do it. If the session is me writing alone, I split my day between the writing and reading aloud what I’ve done so far. I end when I feel the writing’s becoming stale and I need a break. I think knowing when to stop’s an art like anything else.

How many books have you written so far?

I have just finished the manuscript of my ninth poetry collection and am working on my first novel. I’ve also written three books of linked short fictions set in the world of variety. Also, I’ve had published a poetry pilot for schools and three creative writing textbooks and packs. I was fortunate enough to co-author the Victoria and Albert Museum’s creative writing web package with Gillian Spraggs. See below for details:

Volumes and Chapbooks: Poetry

Forthcoming 2019: Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday (King’s England).

Mr Bowlly Regrets (King’s England, 2017)

Napoleon Solo Biscuits (King’s England, 2015)

Volume Using Record Office Collection, Leicester:

Friendship’s Scrapbook (University of Leicester, 2015, reprinted and re-issued as two volumes in 2017, with extracts being published by the University’s Centre for New Writing in Women’s Writing in the Midlands 1750-1850, 2016). Two of the poems were later displayed on the front of Leicester University’s David Wilson Library and in the new Digital Resource Centre, for International Women's Day, 2018. ‘A Walk with Susanna Watts’ from the collection also appeared in Welcome to Leicester (Dahlia Publishing, 2016). Two Responses to the poems, plus a poem based on images of child migrants appeared in Leicester 2084 AD (CivicLeicester, 2018).

Kinda Keats (Shoestring, 2013): Inspired by Residency at Keats House, Hampstead.

Revudeville (King’s England, 2011): Featured many poems inspired by adult and school museum workshops.

Mytton … Dyer … Sweet Billy Gibson (Nine Arches, 2011). Three portraits in verse.

Pavilion (Smokestack, 2010). Poems set in Brighton and featuring images of Dandies.

Clark Gable in Mansfield (King’s England, 2003)

Selected Poems:

Take Five (Shoestring, 2003); The Staring Owl: An Anthology of Poems by the Poets of the King’s England Press (King’s England, 2017)

Special Museum Volume:

Ballad of Epping and Other Poems (Leicestershire Open Museum Pilot, 2007-2008)

Three linked books of short stories set in the 1940s/ 1950s/ 1960s world of variety:

Turned Out Nice Again (King’s England, 2013),

Mice That Roared (King’s England, 2015),

Brand New Beat (King’s England, 2017).

Museum and Education Volumes:

Words and Things: Writing Creatively from Objects and Art (with Mark Goodwin et al, Leicestershire County Council, 2008).

Speaking Words: Writing for Reading Aloud (Crystal Clear, 2005),

Poetry, Prose, and Playfulness for Teachers and Learners (with Mark Goodwin, Leicestershire County Council, 2004).

Museum Packs:

Leicestershire and Nottingham museums (includes Art and Education packs for Leicester’s Open Museum).

Special Commission, Victoria and Albert Museum:

Co-authored creative writing adult education web-package for the Victoria and Albert Museum with Gillian Spraggs, which included two of my poems on objects, these have since been used for summer schools at Wake Forest University, NC, USA and elsewhere.

See also Wellcome Collection work at the British Society for the History of Science (BSHS).

What is your latest book about?

It’s called Mr Bowlly Regrets, is a book of poems, and came out from King’s England Press in 2017. It has many poems about growing up, memory, and change, some on performers, including Britain’s Bing Crosby, the wonderful Al Bowlly. It also contains a sequence on the First World War, which came from a series of Lottery Funded workshops done for Diseworth and other Leicestershire villages. Those poems often contain images of real soldiers from the villages’ war memorials.

I’ve also just completed a further volume of poems for King’s England, Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday which is due out later in 2019. The poems are mainly about theatre and imagery from the lives of Music Hall and Variety performers – of which an elegy for Ken Dodd (to my mind the last of the Victorian inspired performers) is key to the rest of the poems.

On top of these, I’m working on my first novel, Livin’ in a Great Big Way, for the same publisher. This tells the story of Dad, Rosa, and their daughter, Spring, who live on Velia Street, Sutton-in-Ashfield. When the novel opens it’s 1946. Spring’s beloved Aunt, Reena, is dying, and her husband, Nev, is just back from service in Italy. The family have kept things buttoned-up throughout the war, but as Reena fades, secrets and confessions begin spilling out. Also, Dad has visions of moving up in the world, while Rosa’s happy where she is. This is not to mention Grandad Stocks who lives with Mrs Close, much to the family’s shame, Mrs Jim, next door neighbor and Velia Street’s beating heart, and Butcher Mr Cole and his odd wife – whose dreadful crime will come to haunt them all.

How long did it take you to write the book?

My forthcoming book of poems has taken me a couple of years but, interestingly-enough, some of the poems are earlier ones I had in magazines and have since re-written. The poems in Mr Bowlly, likewise, took a couple of years to write, and King’s England published it in 2017. The novel was begun on the way back from the Callander Poetry Weekend in Scotland, in 2017. At first, I thought it was a short story, but it got longer and longer. So, in the end I had to admit it was a novel and carry on!

How did you chose a publisher for the book? Why this publisher? What advantages and/or disadvantages has this presented? How are you dealing with these?

Over the years I’ve had many publishers including Shoestring Press, Smokestack, University of Leicester Press, Leicester County Council Press, Nine Arches Press, and others. But the majority-of my stories and poems have been published by King’s England Press, Huddersfield, under direction of Steve Rudd. When they accepted my first volume of poems, Clark Gable in Mansfield in 2003, they published mainly historic and children’s books. Over years their poetry and fiction lists have grown, and I’ve come to trust Steve’s judgement as an editor. He’s allowed me a lot of consultation on how the volumes look, and how my poetry and prose is presented. He’s also allowed me to experiment and been honest over what did and didn’t work. So, I’ve enjoyed working with him and continue to do so.

Which aspects of the work you put into the book did you find most difficult? Why do you think this was so? How did you deal with these difficulties?

I think with most of my books of poems I deal with memory and characters a lot. I want the poems to be true to the ‘voices’ of various narratives and narrators. So, I think about who sees, who speaks, and period detail as I work. In Mr Bowlly, I wanted the title poem to bring Al Bowlly’s life, the fact he’s such a great performer and yet didn’t get his fair dues from history (he died in 1941 during the blitz, is buried in a communal grave, and has a blue plaque but no statue), and his wonderful singing voice to life. In performance I sing bits of the poem. If someone comes away from reading the volume to watch a clip of him on YouTube, I’ll be happy.

Which aspects of the work did you enjoy most? Why is this?

I enjoyed playing with poetic form in Mr Bowlly – there are sonnets, monologues in rhyming couplets, shaped poems, a poem to the rhythm Longfellow uses in ‘Hiawatha’, unrhymed couplets, and poems chiefly in dialogue. I love playing with form and have previously used sestinas and villanelles, which I go back to in my forthcoming book. Form really tests you, makes you think, and alters the poetic ‘voice.’ I review many poetry books and always feel a bit cheated when a poet doesn’t stretch themselves via form. Lots of unrhymed ‘free verse’ (like many poems I find the term doesn’t really describe what a verse with structures you come up with is) can feel much the same to me. So, I like testing the limits of a poem, and form helps me do this.

What sets the book apart from other things you’ve written?

Although most books represent developments and, hopefully, advancements in style and technique, I think Mr Bowlly differed in that I wanted the sections of the book to be read in tandem, but also stand alone.

I also think I dealt with the subject matter of the First World War in a more sequential way. Those poems were important to me as they dealt with histories of real soldiers that I came across during my workshops and I really wanted to get things right. I also realised that I used the poems to memorialise people who may not have got much of a memorial in death, a technique I began with an earlier poem about my Great Grandad’s son – ‘James William Gibson’ (in Mytton …Dyer …Sweet Billy Gibson) – who died in infancy and was buried below the cemetery wall. The soldiers I came across and used in poems for this newer volume often came from Institutions like the Industrial Schools, so, their next of kin might be their last employer.

In what way is it similar-to the others?

I think I’ve looked at similar histories and voices throughout my poetic career – maybe I’m fascinated with the ‘little things’ in history (both familial and wider) which, as my friend Ray Gosling once remarked, might be more important than the big things.

What will your next book be about?

As this will be the novel, I’d say about family life, of the triumphs and tragedies of human beings being able to live and work together. I realised, also, that the book has a lot of images of craft, (sewing, making, cooking etc.) that may go un-sung as a talent because people separate if from art. I collect vintage items from the 1940s, and often go to 1940s events, loving the music, endurance, and style of the period. Talking to historians and re-enactors (there are some splendid displays on the Home Front, from wedding dresses to the contents of a larder) has made me aware that making something from nothing is a skill to celebrate and venerate – yet often it’s passed-over in favour of the more showy-and-expensive object.

I have begun collecting brooches made by women (started when Mum gave me a brooch made by my Great Aunt from fuse wire, a belt buckle, and buttons shaped like flowers) and marvel at the artistry they create from things you would throw away. I wanted the novel to celebrate craft as someone’s art, their talent, and love – hence Reena in the book is a wonderful seamstress, and Mrs Jim comments at what she might have achieved with money behind her.

What would you say has been your most significant achievement as a writer?

I think, like most writers it’s carrying on writing. Not many people get to do what they love every day, and I think that’s something to be celebrated and, also, marveled at. Obviously, getting published is significant, as it gives your voice an audience, and I hope never to take this for granted. I’ve also been very lucky in the places I’ve worked and read in from the Wellcome Trust, Brighton Pavilion, and Keats House in Hampstead (where I did a residency), to small art galleries, schools and colleges – I wouldn’t have guessed, early on, that I’d work for any of them.

You have a poem featured in Bollocks to Brexit: An Anthology of Poems and Short Fiction. How did the poem come about?

I was tremendously pleased to be asked to be in the book and another poem on Brexit, ‘Ennui’, appears in my new collection. As a writer and someone who has always considered themselves a European, the divisions occasioned by Brexit have made me tremendously sad. I think that the poem, which I wrote especially for the volume, gave me an opportunity to highlight these divisions as they seem to me.

I hope the poem gives you a whistle-stop tour of what I observed after the vote, and how I consider it is the young who will suffer loss of opportunities, from which European Citizens such as myself benefited, from this most disastrous decision. When you feel that your voice is not being heard above shouting – poetry can give you your voice back.

Why is it important for poets to speak up on social, political and related matters?

Poetry has always spoken out on such matters! From Shelley to Blake, Suffragette poets to John Cooper Clarke, poets speak for themselves but also often for the excluded, and those finding themselves ‘voiceless.’

I think it’s worth considering that people sometimes remember lines from a poem giving protest, such as poems by Sassoon, Owen, and Graves from the First World War and those lines come to represent certain times in history perhaps more poignantly than anything else.

What do anthologies like Bollocks to Brexit add to poetry and public discourse?

In a time of shouting, it’s important to hear something more measured, and in a time when phrases such as ‘will of the people’ are being bandied about, it’s a good thing to remember that not all ‘people’ are being represented. You can read a poem over-and-over again, and think about it, come back to it. I always thought Barrack Obama sounded a better statesman than most, because I felt he’d considered his words with care.

Poetry considers its words with care.

Seamus Heaney talked of the right words in their proper places. I think public discourse, at present, is lacking in thoughtful, measured words. Perhaps it’s up to poetry to fill-in the gap.

Showing posts with label novels. Show all posts

Showing posts with label novels. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 24, 2019

Friday, July 19, 2019

Interview _ Deborah Tyler-Bennett

Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s forthcoming volume, Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday, is out from King’s England Press in 2019, and her first novel, Livin’ In a Great Big Way is in preparation for the same publisher. She also has two recent volumes from the same publisher – Mr Bowlly Regrets – Poems, and Brand New Beat: Linked Short Fictions Set in the 1960s (both 2017).

She’s had seven collections of poetry published, some previous volumes being Napoleon Solo Biscuits (King’s England, 2015), poems based on growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, and Kinda Keats (Shoestring, 2013), work deriving from a residency at Keats House, Hampstead.

Her first collection of linked, 1940s set, short stories, Turned Out Nice Again came out from King’s England in 2013, and a sequel, set in the 1950s, Mice that Roared was published in 2015, Brand New Beat, set in the 1960s, represents the final part of the trilogy.

In 2016, The Coffee House Anthology from Charnwood Arts marked the final volume of Coffee House magazine, which she edited for twenty-five issues over fifteen years (this was featured on the Poetry Society’s poetic map of England).

Translations and publications of her poems have appeared in Spain, Ireland, The US, Scotland, Austria, and Romania, where they were broadcast on Radio Bucharest. She’s also read in Belgium.

Deborah regularly reviews poetry and has written books and education packs on creative writing.

Recent poems have appeared in the anthologies Double Bill (Red Squirrel, 2014), Maps and Legends (Nine Arches, 2013), Strike Up the Band: Poems for John Lucas at Eighty (Plas Gwyn Books, 2017), and the Max Miller Society journal, who recently published the elegy for Ken Dodd that forms the title poem in her new book. New poems appear in Leicester 2084 AD (CivicLeicester, 2018).

She regularly performs her work and has appeared at many venues in Brighton, London, the East Midlands and nationally. She occasionally teams up with music hall expert Ann Featherstone to perform variety stories from her first two collections. She also does many workshops for adult and school groups, teaches writing classes for the WEA, and hosts workshops for national galleries and museums.

In 2018 one of her poems was displayed on the side of Leicester University Library, and one at its new digital resource centre, for International Women’s Day.

With Gillian Spraggs, she co-authored the Victoria and Albert Museum’s creative writing web pages. She’s also currently working on a new poetic sequence, The Ladies of Harris’s List set in the eighteenth-century, and a series of music hall poems with Andy Jackson.

In this interview, Deborah Tyler-Bennett talks about her writing:

When did you start writing?

I’ve been writing things down for as long as I can remember being able to write and recall composing poems and bits of stories from the age of about eight. I don’t think I started taking the writing seriously until I was in my early twenties. Then you realise you’re starting to have drawers and notebooks full of stuff and you need to do something creative with it. I don’t think I felt I’d earned being called a ‘writer’ until I’d had a significant amount of work published.

How did you decide you wanted to be a published writer?

I think the above realisation (that you have lots of work and unless someone else gets to read it, it’s a little pointless, and also you have no feedback on what others think of it) drives you to send work out. Personally, I began sending poems to little magazines and competitions. I felt that if I had a body of published work behind me, and people responded to it, then maybe I could send work away for consideration as a collection.

The more I had published in little magazines, the more I felt I was becoming part of a poetic community and, also, most crucially, the more I learned. Editors sending advice and encouragement was invaluable to me. I also considered the range of where I sent to – I had quite a few things published in Ireland and found the magazines there an aesthetic delight. To achieve publication takes a thick skin and the old cliché about all writers getting used to rejections is true – but these make the publications you do get, sweeter.

How would you describe the writing you are doing?

I think my writing has changed a lot over the years. At-the-moment, I’ve just finished my ninth volume of poetry and am working on new poems. I’m also writing my first novel. This comes after three volumes of linked short stories. It’s always hard to describe your own work but I think I’ve become fascinated by the lives of so-called ‘ordinary’ people – and have come to believe that no one has an ‘ordinary life.’

I think writing is a great way of conveying past and present – and have noticed two things, recently, in commentaries on my work. Firstly, people comment on my use of Nottinghamshire dialect, as if it’s something unusual to use. Secondly, people often think I’ve invented elements that come from my own background and family history. I feel as if we’re living at a cultural time where, if we’re not careful, and despite the success of writers like Sally Wainwright and Andrew Graves on the script writing and poetry scenes, we’ll be going back to the idea of the arts as a preserve of the privileged and socially connected.

I realise what’s not unusual for me, seems unusual to some, and that there are many assumptions made about writing from ‘ordinary’ life.

I’m also using a lot of images and characters from music hall in my poetry (my new book’s titled Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday) as I do think that this reflects a type of history that often gets ignored, sidelined, or damned with the loaded phrase ‘popular culture.’

I’ve also started to take my painting more seriously and exhibit work and suspect that the colours and textures I use in visual art creep into my poems and stories.

Who is your target audience?

This question is interesting. When I started, I don’t think I thought in terms of a ‘target audience.’ Most poets I know are just glad to get an audience. But I do think over time I’ve become aware that with poetry in particular - I want my work to be accessible to the widest possible audience. I don’t really want someone to leave a reading of mine saying: “I didn’t get it.” Or “I think that was aimed at a poetry or literary-critical group.”

The same is also true of fiction. I like it when an audience laughs, holds its breath, or even joins-in. Maybe that’s the music hall influence again. I like it even more when someone approaches me after a reading to say that they didn’t think poetry was for them, but they enjoyed what I did and would go to a reading again. I try my stories out on local audiences, or reading them aloud at home, and hope that anyone who wanted to read something could do so without fear of being either talked at, down to, or addressed in a jargon clearly meant for a specific crowd.

In the writing you are doing, which authors influenced you most?

Like most writers, I love so many authors (both classic and contemporary) that it’s hard to narrow it down. I think the biggest influence on my poetry and storytelling has been the Orkney writer George Mackay Brown. He wrote novels, stories, poems, a column for his local paper, libretti, dramas and work for festivals. He could catch how people spoke, vibrant imagery of time and place and was fascinated by blurring boundaries between chronological periods. And his images are so vital, instead of saying someone was hungover he describes them as having a mouth ‘full of ashes’, lipstick imprinting a man’s cheek becomes ‘red birds’ – magic!

There are so many contemporary poets I admire, and I like those such as Emma Lee and Andrew Graves who are always experimenting and pushing the boundaries of what they do. Simon Armitage, Mark Goodwin, and John Hegley make me question how I write and what I can learn from people experimenting with language. Carol Leeming makes me think of how I perform and how I can do more, as do Ian Macmillan, Benjamin Zephaniah, and others. John Cooper Clarke, obviously, has an unmatchable status as performer and writer, I’ve always loved watching, hearing and reading him. I think it was Mark E. Smith of The Fall who said he didn’t wholly trust people who didn’t like John Cooper Clarke, and I think that’s sound (oh, that, and Elvis, too).

In prose, I’m still a huge fan of Dickens, as I think he tells such memorable stories full of such vibrant oddities. I did a PhD thesis on Djuna Barnes, and still find her work extraordinary. One book that I’ve found my most re-read is an anthology by John Sampson called The Wind on the Heath, about gypsies and published in the nineteen twenties. The stories and poems in it sing.

Likewise, I write a lot of ghost stories and am a huge fan of the form, loving E. Nesbit, Mary E. Braddon, Dickens, M.R. James, Ian Blake, and Susan Hill. Stars all. I think ghost stories are hard but worth it and reading around the genre helps you know your way around the structures of it. I swap ghost stories with Scottish writer, Ian Blake, and we enjoy a correspondence over the genre.

Sally Evans who edited Poetry Scotland has been a huge influence on my work, reading techniques, and has inspired me as a poet. Her poems do so much within economic lines and lingering images and I’ve never met anyone so welcoming and generous to her fellow poets. For years she and Ian King ran the Callander Poetry Weekend and it was a joy to attend and perform at that.

Lastly, I love European writing, and have always considered myself blessed as a writer to be part of Europe. The culture which includes writers as diverse as Balzac, Marco Vici, Hugo and Colette is an ever self-enriching one, and we have been fortunate indeed to be part of that.

How have your own personal experiences influenced your writing?

I think even if your telling of a certain story doesn’t seem connected to your own life experience, that experience will be embedded in this somewhere. Sometimes stories come directly from my family history, places travelled or lived in, or people met. Other stories might seem removed from the above, but actually- have elements of my experience in them.

I think even if your telling of a certain story doesn’t seem connected to your own life experience, that experience will be embedded in this somewhere. Sometimes stories come directly from my family history, places travelled or lived in, or people met. Other stories might seem removed from the above, but actually- have elements of my experience in them.

Occasionally I write from a current event, and it’s true that living in ‘interesting times’ (a polite way of saying that you turn the news on every night wondering what on earth could have happened today) these ‘event’ based poems grow in number. Over the past year I’ve written poems as responses to the disaster of Brexit and about how lack of empathy leads people to disregard what’s happening to fellow human beings in front of their noses.

Even a poem based in the nineteenth century (‘The Boy Acrobat’s Villanelle’ published in Leicester 2084 AD) ended with an image of twenty-first century child migrants, children whose Dickensian plight can only be ignored via a spectacular lack of empathy.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Like most writers, I want to tell a story (whether in poetry or prose) well, and make the reader feel that the read was worth it. I also like putting people and places before the reader that come from my own growing-up, family stories, and local legends. I became aware in my late teens that my Grandma’s language, her bit of Nottinghamshire, and the world she grew up in, was vanishing. Like George Mackay Brown’s Orkney, I wanted to get some of it down before it went all together.

When I was writing my three volumes of stories set in variety, I had a desire to make the reader’s emotional response to the short fictions similar to those they’d get in a theatre – a story might bring a lump to your throat one minute and make you laugh in the next.

As with all such techniques and concerns, writers just have-to keep going, and I know whatever I’ve planned the story might well have other ideas. During the variety stories, an old lady, Grandwem (a cross between my Grandma and Great Aunt, plus some others) was going to be a minor character. She had other ideas and became the mainstay of all three books, the glue holding the family together.

In my current novel, the plan I’d made crashed and burned as a minor character did something awful as I wrote, and I had to go back and revise the whole first part of the book! Like painting, I love the unknown element that creeps in when you write, making me think of the old blues adage: ‘Make God laugh, tell him all your plans.”

What are the biggest challenges that you face? And, how do you deal with them?

I think for writers, challenges can be divided into practical working challenges, and aesthetic challenges.

The second category includes the obvious thing of being true to your ‘voice’ and the stories and poetic narratives you want to tell. In other words, it’s easy to become distracted from your purpose, think there are more fashionable things you could be writing, or forget why you wanted to tell a certain story in the first place. I’ve found it very useful to stop from time-to-time and ask: ‘why did you want to write this?’ I also find Robert Graves idea of ‘the reader over your shoulder’ very useful. Imagine someone looking at your work ‘over your shoulder’ – ask ‘what will they get out of it?’ If the answer is ‘not enough’ then that’s the time for a re-write or re-vision.

The first category I mentioned - the practical working challenge - may cover several bases. How much money do you need to earn to keep writing? Where does funding come from? How much time a week do you spend actually-writing? Is this time enough?

Due to current events, arts funding is going to become tighter, outreach for writers lessening as they are excluded from European opportunities, and I foresee writers who flourish will be previously established, have to work many more hours to stay afloat, or have private incomes and connections.

Reading information from literary bodies already indicates as much. I hope I’m wrong, and that writers beginning as I did from ordinary schools and backgrounds will have opportunities similar to mine. But I think most writers from state schools will struggle more, and that all writers will face challenges we couldn’t have seen prior to 2017. The challenge is (to mis-quote a US President) to do it because it is hard, to do it because it is there – to do it because that’s what you do. And (to misquote a US boxing legend) if you do what you love, strive to be the best at it you can be.

She’s had seven collections of poetry published, some previous volumes being Napoleon Solo Biscuits (King’s England, 2015), poems based on growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, and Kinda Keats (Shoestring, 2013), work deriving from a residency at Keats House, Hampstead.

Her first collection of linked, 1940s set, short stories, Turned Out Nice Again came out from King’s England in 2013, and a sequel, set in the 1950s, Mice that Roared was published in 2015, Brand New Beat, set in the 1960s, represents the final part of the trilogy.

In 2016, The Coffee House Anthology from Charnwood Arts marked the final volume of Coffee House magazine, which she edited for twenty-five issues over fifteen years (this was featured on the Poetry Society’s poetic map of England).

Translations and publications of her poems have appeared in Spain, Ireland, The US, Scotland, Austria, and Romania, where they were broadcast on Radio Bucharest. She’s also read in Belgium.

Deborah regularly reviews poetry and has written books and education packs on creative writing.

Recent poems have appeared in the anthologies Double Bill (Red Squirrel, 2014), Maps and Legends (Nine Arches, 2013), Strike Up the Band: Poems for John Lucas at Eighty (Plas Gwyn Books, 2017), and the Max Miller Society journal, who recently published the elegy for Ken Dodd that forms the title poem in her new book. New poems appear in Leicester 2084 AD (CivicLeicester, 2018).

She regularly performs her work and has appeared at many venues in Brighton, London, the East Midlands and nationally. She occasionally teams up with music hall expert Ann Featherstone to perform variety stories from her first two collections. She also does many workshops for adult and school groups, teaches writing classes for the WEA, and hosts workshops for national galleries and museums.

In 2018 one of her poems was displayed on the side of Leicester University Library, and one at its new digital resource centre, for International Women’s Day.

With Gillian Spraggs, she co-authored the Victoria and Albert Museum’s creative writing web pages. She’s also currently working on a new poetic sequence, The Ladies of Harris’s List set in the eighteenth-century, and a series of music hall poems with Andy Jackson.

In this interview, Deborah Tyler-Bennett talks about her writing:

When did you start writing?

I’ve been writing things down for as long as I can remember being able to write and recall composing poems and bits of stories from the age of about eight. I don’t think I started taking the writing seriously until I was in my early twenties. Then you realise you’re starting to have drawers and notebooks full of stuff and you need to do something creative with it. I don’t think I felt I’d earned being called a ‘writer’ until I’d had a significant amount of work published.

How did you decide you wanted to be a published writer?

I think the above realisation (that you have lots of work and unless someone else gets to read it, it’s a little pointless, and also you have no feedback on what others think of it) drives you to send work out. Personally, I began sending poems to little magazines and competitions. I felt that if I had a body of published work behind me, and people responded to it, then maybe I could send work away for consideration as a collection.

The more I had published in little magazines, the more I felt I was becoming part of a poetic community and, also, most crucially, the more I learned. Editors sending advice and encouragement was invaluable to me. I also considered the range of where I sent to – I had quite a few things published in Ireland and found the magazines there an aesthetic delight. To achieve publication takes a thick skin and the old cliché about all writers getting used to rejections is true – but these make the publications you do get, sweeter.

How would you describe the writing you are doing?

I think my writing has changed a lot over the years. At-the-moment, I’ve just finished my ninth volume of poetry and am working on new poems. I’m also writing my first novel. This comes after three volumes of linked short stories. It’s always hard to describe your own work but I think I’ve become fascinated by the lives of so-called ‘ordinary’ people – and have come to believe that no one has an ‘ordinary life.’

I think writing is a great way of conveying past and present – and have noticed two things, recently, in commentaries on my work. Firstly, people comment on my use of Nottinghamshire dialect, as if it’s something unusual to use. Secondly, people often think I’ve invented elements that come from my own background and family history. I feel as if we’re living at a cultural time where, if we’re not careful, and despite the success of writers like Sally Wainwright and Andrew Graves on the script writing and poetry scenes, we’ll be going back to the idea of the arts as a preserve of the privileged and socially connected.

I realise what’s not unusual for me, seems unusual to some, and that there are many assumptions made about writing from ‘ordinary’ life.

I’m also using a lot of images and characters from music hall in my poetry (my new book’s titled Ken Dodd Takes a Holiday) as I do think that this reflects a type of history that often gets ignored, sidelined, or damned with the loaded phrase ‘popular culture.’

I’ve also started to take my painting more seriously and exhibit work and suspect that the colours and textures I use in visual art creep into my poems and stories.

Who is your target audience?

This question is interesting. When I started, I don’t think I thought in terms of a ‘target audience.’ Most poets I know are just glad to get an audience. But I do think over time I’ve become aware that with poetry in particular - I want my work to be accessible to the widest possible audience. I don’t really want someone to leave a reading of mine saying: “I didn’t get it.” Or “I think that was aimed at a poetry or literary-critical group.”

The same is also true of fiction. I like it when an audience laughs, holds its breath, or even joins-in. Maybe that’s the music hall influence again. I like it even more when someone approaches me after a reading to say that they didn’t think poetry was for them, but they enjoyed what I did and would go to a reading again. I try my stories out on local audiences, or reading them aloud at home, and hope that anyone who wanted to read something could do so without fear of being either talked at, down to, or addressed in a jargon clearly meant for a specific crowd.

In the writing you are doing, which authors influenced you most?

Like most writers, I love so many authors (both classic and contemporary) that it’s hard to narrow it down. I think the biggest influence on my poetry and storytelling has been the Orkney writer George Mackay Brown. He wrote novels, stories, poems, a column for his local paper, libretti, dramas and work for festivals. He could catch how people spoke, vibrant imagery of time and place and was fascinated by blurring boundaries between chronological periods. And his images are so vital, instead of saying someone was hungover he describes them as having a mouth ‘full of ashes’, lipstick imprinting a man’s cheek becomes ‘red birds’ – magic!

There are so many contemporary poets I admire, and I like those such as Emma Lee and Andrew Graves who are always experimenting and pushing the boundaries of what they do. Simon Armitage, Mark Goodwin, and John Hegley make me question how I write and what I can learn from people experimenting with language. Carol Leeming makes me think of how I perform and how I can do more, as do Ian Macmillan, Benjamin Zephaniah, and others. John Cooper Clarke, obviously, has an unmatchable status as performer and writer, I’ve always loved watching, hearing and reading him. I think it was Mark E. Smith of The Fall who said he didn’t wholly trust people who didn’t like John Cooper Clarke, and I think that’s sound (oh, that, and Elvis, too).

In prose, I’m still a huge fan of Dickens, as I think he tells such memorable stories full of such vibrant oddities. I did a PhD thesis on Djuna Barnes, and still find her work extraordinary. One book that I’ve found my most re-read is an anthology by John Sampson called The Wind on the Heath, about gypsies and published in the nineteen twenties. The stories and poems in it sing.

Likewise, I write a lot of ghost stories and am a huge fan of the form, loving E. Nesbit, Mary E. Braddon, Dickens, M.R. James, Ian Blake, and Susan Hill. Stars all. I think ghost stories are hard but worth it and reading around the genre helps you know your way around the structures of it. I swap ghost stories with Scottish writer, Ian Blake, and we enjoy a correspondence over the genre.

Sally Evans who edited Poetry Scotland has been a huge influence on my work, reading techniques, and has inspired me as a poet. Her poems do so much within economic lines and lingering images and I’ve never met anyone so welcoming and generous to her fellow poets. For years she and Ian King ran the Callander Poetry Weekend and it was a joy to attend and perform at that.

Lastly, I love European writing, and have always considered myself blessed as a writer to be part of Europe. The culture which includes writers as diverse as Balzac, Marco Vici, Hugo and Colette is an ever self-enriching one, and we have been fortunate indeed to be part of that.

How have your own personal experiences influenced your writing?

I think even if your telling of a certain story doesn’t seem connected to your own life experience, that experience will be embedded in this somewhere. Sometimes stories come directly from my family history, places travelled or lived in, or people met. Other stories might seem removed from the above, but actually- have elements of my experience in them.

I think even if your telling of a certain story doesn’t seem connected to your own life experience, that experience will be embedded in this somewhere. Sometimes stories come directly from my family history, places travelled or lived in, or people met. Other stories might seem removed from the above, but actually- have elements of my experience in them. Occasionally I write from a current event, and it’s true that living in ‘interesting times’ (a polite way of saying that you turn the news on every night wondering what on earth could have happened today) these ‘event’ based poems grow in number. Over the past year I’ve written poems as responses to the disaster of Brexit and about how lack of empathy leads people to disregard what’s happening to fellow human beings in front of their noses.

Even a poem based in the nineteenth century (‘The Boy Acrobat’s Villanelle’ published in Leicester 2084 AD) ended with an image of twenty-first century child migrants, children whose Dickensian plight can only be ignored via a spectacular lack of empathy.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Like most writers, I want to tell a story (whether in poetry or prose) well, and make the reader feel that the read was worth it. I also like putting people and places before the reader that come from my own growing-up, family stories, and local legends. I became aware in my late teens that my Grandma’s language, her bit of Nottinghamshire, and the world she grew up in, was vanishing. Like George Mackay Brown’s Orkney, I wanted to get some of it down before it went all together.

When I was writing my three volumes of stories set in variety, I had a desire to make the reader’s emotional response to the short fictions similar to those they’d get in a theatre – a story might bring a lump to your throat one minute and make you laugh in the next.

As with all such techniques and concerns, writers just have-to keep going, and I know whatever I’ve planned the story might well have other ideas. During the variety stories, an old lady, Grandwem (a cross between my Grandma and Great Aunt, plus some others) was going to be a minor character. She had other ideas and became the mainstay of all three books, the glue holding the family together.

In my current novel, the plan I’d made crashed and burned as a minor character did something awful as I wrote, and I had to go back and revise the whole first part of the book! Like painting, I love the unknown element that creeps in when you write, making me think of the old blues adage: ‘Make God laugh, tell him all your plans.”

What are the biggest challenges that you face? And, how do you deal with them?

I think for writers, challenges can be divided into practical working challenges, and aesthetic challenges.

The second category includes the obvious thing of being true to your ‘voice’ and the stories and poetic narratives you want to tell. In other words, it’s easy to become distracted from your purpose, think there are more fashionable things you could be writing, or forget why you wanted to tell a certain story in the first place. I’ve found it very useful to stop from time-to-time and ask: ‘why did you want to write this?’ I also find Robert Graves idea of ‘the reader over your shoulder’ very useful. Imagine someone looking at your work ‘over your shoulder’ – ask ‘what will they get out of it?’ If the answer is ‘not enough’ then that’s the time for a re-write or re-vision.

The first category I mentioned - the practical working challenge - may cover several bases. How much money do you need to earn to keep writing? Where does funding come from? How much time a week do you spend actually-writing? Is this time enough?

Due to current events, arts funding is going to become tighter, outreach for writers lessening as they are excluded from European opportunities, and I foresee writers who flourish will be previously established, have to work many more hours to stay afloat, or have private incomes and connections.

Reading information from literary bodies already indicates as much. I hope I’m wrong, and that writers beginning as I did from ordinary schools and backgrounds will have opportunities similar to mine. But I think most writers from state schools will struggle more, and that all writers will face challenges we couldn’t have seen prior to 2017. The challenge is (to mis-quote a US President) to do it because it is hard, to do it because it is there – to do it because that’s what you do. And (to misquote a US boxing legend) if you do what you love, strive to be the best at it you can be.

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Interview _ Tony R. Cox

Novelist and short story writer, Tony R. Cox was a reporter at the Derby Evening Telegraph in the 1970s, and a Business Editor at the Nottingham Evening Post in the late 70s before moving to public relations and running his own business-to-business consultancy.

He is the author of the crime thriller novels, First Dead Body (The Choir Press, 2014) and A Fatal Drug (Fahrenheit Press, 2016), both of which are set in Derby. First Dead Body has been described as encapsulating "the life of 1970s reporters when lunches were often long and liquid and it was the norm to meet contacts in pubs like The Dolphin, The Exeter Arms, The Wagon and Horses." While in First Dead Body, the action takes place in Derby, in A Fatal Drug, an investigation into the discovery of a mutilated body reveals a spiral of gangland drug dealing and violence that stretches from the north of England to the south of Spain.

In this interview, Tony R. Cox talks about his writing.

When did you start writing?

I was editor of the school magazine; a regional journalist for 15 years; 25 years in public relations, mainly writing for newspapers and magazines nationally and internationally.

In 2010, after I’d decided to semi-retire, it was suggested that I write a memoir of what I used to get up to in the early 70s when I was heavily involved in rock and jazz music reviews and everything that went with it. That formed the kernel of an idea for a novel. I self-published First Dead Body in 2014, basically because I didn’t want the hassle (and ignominy of being rejected) of finding a publisher. After my first novel came out, I vowed never to self-publish (I’m a writer, not a salesman) and researched potential publishers. I approached Fahrenheit Press as they seemed like a good fit and was taken on. My second novel, A Fatal Drug, was published in 2016.

How would you describe the writing you are doing?

I write crime thrillers with a historical (1960s and 70s) slant. My protagonists are journalists who are drawn into the action; the police are present, but these are not ‘police procedurals’.

I hope my books appeal to anybody who enjoys crime fiction.

I was told a while ago: “Write about what you know”. I hope my knowledge of the early 70s and newspapers is interesting.

I was in my 20s all the way through the 70s, and memories are vivid. I also lived in Pakistan in the very early 60s; and then worked as a journalist during what I believe were the last great days of regional newspapers.

Which authors influenced you most?

All crime writers help, but I try and follow the characterisation and description that is accomplished so brilliantly by people like Ian McEwan, Alan Sillitoe, James Joyce and, of course, the maestro, Ian Rankin.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Cadence and coherence, mainly. I believe every book must capture the reader and lead them through, gradually as the pace quickens.

What are the biggest challenges that you face?

Getting it right! Money is not the prime objective, nor is becoming a best-seller, but I want my books to be accepted as well-written.

Do you write everyday?

No way. I write frenetically to get the plot down and this can be a base of about 50,000 to 70,000 words. Then I stop; put it away; go and re-visit the locations; immerse myself in the people. After a week or a month I go back and start the heavy edit, which is basically re-writing the novel from scratch, but with a structure already in place.

In addition to novels, you also write short stories. Do you use the same approach to short stories as you use when you are writing novels?

One of my short stories, "Under a Savage Sky" was published by Dahlia Publishing in Lost and Found in mid-2016. Another, "A Cup of Cold Coffee and a Slice of Life" was published by Bloodhound Books as part of the international anthology Dark Minds, with all proceeds going to charity.

Short stories and novels are very different and, for me, require a different approach. With novels, I find that the reader must be ‘captured’ early on and then gradually drawn through, their attention being maintained, a series of literary undulations leading to a constantly hinted at climax. With short stories, setting the scene and introducing vivid characterisation is vital. The plot is reasonably straightforward from the outset and is developed during the story; the finale needs to have a subtle, or even dramatically obvious, twist. A sort of ‘Agh!’ moment.

How would you describe A Fatal Drug?

A Fatal Drug follows the newspaper journalist's hunt for a front page lead through murder and torture, drug smuggling and the bid by villains to established a drugs supply business. The book was plotted in 2015, but then went through a very severe re-write, then an extended edit.

It was published by Fahrenheit Press and is available on Amazon as an Ebook (April 2016) and a paperback (September 2016).

Why Fahrenheit Press? What advantages or disadvantages has this presented?

Fahrenheit Press do things differently. When I approached them they were digital only and based their operation on Twitter ‘storms’ and a ‘book club’. The small stable of authors appealed in terms of genre (all crime fiction).

There were two initial disadvantages: Firstly, A Fatal Drug would not be printed, but be an ebook; and, secondly, it would not be on sale in high street shops. The first of these was handled after they’d read my manuscript and decided it would be printed; the second, I had to take on the chin, but the novel is still available – and selling – as a paperback through Amazon.

Which aspects of the work you put into the book did you find most difficult?

The time factor is not as easy as I first thought. Clothing styles were never of any interest, so I had to read books of that time and absorb magazines of that era.

Which aspects of the work did you enjoy most?

The fact that my main protagonist is a reporter on a regional newspaper allows me the opportunity to have him doing things that I could only dream of. I really enjoy creating my characters – many of whom are amalgams of people of that time.

What sets A Fatal Drug apart from other things you've written?

This is the second in a series. I hope it is a development of characters and plot.

The main protagonists and locations are the same in A Fatal Drug and First Dead Body, but in A Fatal Drug I take the action out of Derby, whereas, in First Dead Body, it remained in the town.

The next novel in the series will continue with the main characters (not the villains), but will also be much more complex. It starts by examining payola (bribing DJs to play records) and then moves through drug dealing, the Soho-based record industry, to eventually involve the IRA.

What would you say has been your most significant achievement as a writer?

Being accepted by my peers as a writer. I was – and to a certain extent – still am, in awe of authors in all genres. After a career in business, even though it was a creative one, it is wonderful to feel part of a growing and developing creative environment that doesn’t judge, is always supportive, and encourages writers to share and help each other.

He is the author of the crime thriller novels, First Dead Body (The Choir Press, 2014) and A Fatal Drug (Fahrenheit Press, 2016), both of which are set in Derby. First Dead Body has been described as encapsulating "the life of 1970s reporters when lunches were often long and liquid and it was the norm to meet contacts in pubs like The Dolphin, The Exeter Arms, The Wagon and Horses." While in First Dead Body, the action takes place in Derby, in A Fatal Drug, an investigation into the discovery of a mutilated body reveals a spiral of gangland drug dealing and violence that stretches from the north of England to the south of Spain.

In this interview, Tony R. Cox talks about his writing.

When did you start writing?

I was editor of the school magazine; a regional journalist for 15 years; 25 years in public relations, mainly writing for newspapers and magazines nationally and internationally.

In 2010, after I’d decided to semi-retire, it was suggested that I write a memoir of what I used to get up to in the early 70s when I was heavily involved in rock and jazz music reviews and everything that went with it. That formed the kernel of an idea for a novel. I self-published First Dead Body in 2014, basically because I didn’t want the hassle (and ignominy of being rejected) of finding a publisher. After my first novel came out, I vowed never to self-publish (I’m a writer, not a salesman) and researched potential publishers. I approached Fahrenheit Press as they seemed like a good fit and was taken on. My second novel, A Fatal Drug, was published in 2016.

How would you describe the writing you are doing?

I write crime thrillers with a historical (1960s and 70s) slant. My protagonists are journalists who are drawn into the action; the police are present, but these are not ‘police procedurals’.

I hope my books appeal to anybody who enjoys crime fiction.

I was told a while ago: “Write about what you know”. I hope my knowledge of the early 70s and newspapers is interesting.

I was in my 20s all the way through the 70s, and memories are vivid. I also lived in Pakistan in the very early 60s; and then worked as a journalist during what I believe were the last great days of regional newspapers.

Which authors influenced you most?

All crime writers help, but I try and follow the characterisation and description that is accomplished so brilliantly by people like Ian McEwan, Alan Sillitoe, James Joyce and, of course, the maestro, Ian Rankin.

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Cadence and coherence, mainly. I believe every book must capture the reader and lead them through, gradually as the pace quickens.

What are the biggest challenges that you face?

Getting it right! Money is not the prime objective, nor is becoming a best-seller, but I want my books to be accepted as well-written.

Do you write everyday?

No way. I write frenetically to get the plot down and this can be a base of about 50,000 to 70,000 words. Then I stop; put it away; go and re-visit the locations; immerse myself in the people. After a week or a month I go back and start the heavy edit, which is basically re-writing the novel from scratch, but with a structure already in place.

In addition to novels, you also write short stories. Do you use the same approach to short stories as you use when you are writing novels?

One of my short stories, "Under a Savage Sky" was published by Dahlia Publishing in Lost and Found in mid-2016. Another, "A Cup of Cold Coffee and a Slice of Life" was published by Bloodhound Books as part of the international anthology Dark Minds, with all proceeds going to charity.

Short stories and novels are very different and, for me, require a different approach. With novels, I find that the reader must be ‘captured’ early on and then gradually drawn through, their attention being maintained, a series of literary undulations leading to a constantly hinted at climax. With short stories, setting the scene and introducing vivid characterisation is vital. The plot is reasonably straightforward from the outset and is developed during the story; the finale needs to have a subtle, or even dramatically obvious, twist. A sort of ‘Agh!’ moment.

How would you describe A Fatal Drug?

A Fatal Drug follows the newspaper journalist's hunt for a front page lead through murder and torture, drug smuggling and the bid by villains to established a drugs supply business. The book was plotted in 2015, but then went through a very severe re-write, then an extended edit.

It was published by Fahrenheit Press and is available on Amazon as an Ebook (April 2016) and a paperback (September 2016).

Why Fahrenheit Press? What advantages or disadvantages has this presented?

Fahrenheit Press do things differently. When I approached them they were digital only and based their operation on Twitter ‘storms’ and a ‘book club’. The small stable of authors appealed in terms of genre (all crime fiction).

There were two initial disadvantages: Firstly, A Fatal Drug would not be printed, but be an ebook; and, secondly, it would not be on sale in high street shops. The first of these was handled after they’d read my manuscript and decided it would be printed; the second, I had to take on the chin, but the novel is still available – and selling – as a paperback through Amazon.

Which aspects of the work you put into the book did you find most difficult?

The time factor is not as easy as I first thought. Clothing styles were never of any interest, so I had to read books of that time and absorb magazines of that era.

Which aspects of the work did you enjoy most?

The fact that my main protagonist is a reporter on a regional newspaper allows me the opportunity to have him doing things that I could only dream of. I really enjoy creating my characters – many of whom are amalgams of people of that time.

What sets A Fatal Drug apart from other things you've written?

This is the second in a series. I hope it is a development of characters and plot.

The main protagonists and locations are the same in A Fatal Drug and First Dead Body, but in A Fatal Drug I take the action out of Derby, whereas, in First Dead Body, it remained in the town.

The next novel in the series will continue with the main characters (not the villains), but will also be much more complex. It starts by examining payola (bribing DJs to play records) and then moves through drug dealing, the Soho-based record industry, to eventually involve the IRA.

What would you say has been your most significant achievement as a writer?

Being accepted by my peers as a writer. I was – and to a certain extent – still am, in awe of authors in all genres. After a career in business, even though it was a creative one, it is wonderful to feel part of a growing and developing creative environment that doesn’t judge, is always supportive, and encourages writers to share and help each other.

Thursday, February 14, 2013

Interview _ Ellie Stevenson

Ellie Stevenson was born in Oxford and brought up in Australia. She is a member of the Careers Writers' Association and the Alliance of Independent Authors.

Ellie Stevenson was born in Oxford and brought up in Australia. She is a member of the Careers Writers' Association and the Alliance of Independent Authors.She writes feature articles and short stories.

Her first novel, Ship of Haunts: the other Titanic story (Rosegate Publications, 2012), which is available as an e-book and as a paperback, has been described as "engaging and lively ... a real page-turner" and as "thoroughly enjoyable".

In this interview, Ellie Stevenson talks about her concerns as a writer:

When did you start writing?

When I was 10.

I spent part of my childhood in Australia, and I would lie in bed and listen to the sounds of the Australian bush, and think about what I could do with my life. My first published work was a poem published in an Australian state newspaper. Then came a hiatus, quite a long one, but fortunately, that’s over now.

How would you describe your writing?

Fairly eclectic.

Primarily I’m focused on writing more novels but I also write stories, articles and poetry. The poetry's more of a leisure thing, but I like to think it informs my work!

I always wanted to write books, but life and a need for cold, hard cash got in the way. When I finally took my ambition seriously, I started with articles, as a way getting some hands-on experience. But I always planned to be a novelist – I just wasn’t sure if I had the stamina.

Who is your target audience?

Anyone who wants to read my work!

No, seriously, I write for people who love mysteries and a sense of something other-worldly. I love to read ghost stories and books that take us across time and space. Maybe some time travel, or something that haunts or has a bit of a twist.

I write the stories I want to read.

I like novels which speak to the reader, are emotionally strong. And those that challenge the reader’s concepts, while still maintaining a page-turning story. Lyrical language is also important. I love to read books by Maggie O’Farrell and Douglas Kennedy.

Have your own personal experiences influenced your writing in any way?

My novel is a ghost story about Titanic, child migration and living a life under the sea. I’m an historian by nature and I love the past. Three of my family were child migrants and I’ve been heavily influenced by the time I spent living in Australia, an amazing country. I’ve always been passionate about Titanic. As for the ghosts, I can’t really say...

What are your main concerns as a writer?

Making my work the best it can be and improving its rhythm and the way it flows. Having integrity in my stories. Making people wonder if what we know isn’t all there is. Reaching readers.

What are the biggest challenges that you face?

Marketing my work. In order to be read, readers need to know you exist. I enjoy promoting my novel and articles but it takes a lot of time, which means less time to write. It’s a constant trade off, especially if you’re an independent author. Every day I do a little bit more.

Do you write every day?

At the moment I’m focused on promoting the novel. But when I’m writing, yes, every day, in allocated time slots until I have to do something else. I stop at that point, or when I come to a natural break. The initial writing isn’t that hard, the real work comes with the plot corrections, improvements to language, and the many revisions. I’m naturally self-critical and my work is never good enough. It’s not a happy trait for a writer to have!

How many books have you written so far?

One so far, Ship of Haunts, although a collection of short stories will be coming out in late September.

How long did it take you to write the novel?

Far too long. The next one will be quicker.

Where and when was it published?

Initially, as an ebook on Amazon (Rosegate Publications). It was published in April 2012, to coincide with the 100-year anniversary of Titanic’s sinking. Print copies are also available, via Amazon.com, or via me if you live in the UK.

How did you choose a publisher for the book?

Because it took so long to write, and I had to meet the April deadline, an ebook was the obvious choice, with printed copies following later. That’s the beauty of independent publishing: the author has control of the book. It’s also the downside – you have to do all the work yourself. Commissioning a cover, getting it proofed, getting it out there. I’d do it again, but it’s a steep learning curve.

Which were the most difficult aspects of the work that went into Ship of Haunts?

The book was organic, it developed as I wrote it. And then of course, it needed reworking. I spent much of my time rewriting the novel. Again and again. Next time round, I’m planning the book before I write it!

What did you enjoy most?

Creation of the story, thinking of the plotlines, doing the research. The creative side is why I write. Editing and rewrites are hard work, especially when you’re several drafts in.

What sets Ship of Haunts apart from other things you've written?

It’s my first novel, so in that sense it’s totally different. And Titanic, of course, is quite unique. And the novel encompasses reincarnation, which is a little bit out there (in the West, anyway).

In what way is it similar to the others?

The broader themes are fairly similar to the stories I’ve written: mysteries and loss and a sense of something unexpected, perhaps paranormal. The odd twist or a bit of a chill...

What will your next book be about?

A lost place and a man who... (well that would be telling)

What would you say has been your most significant achievement as a writer?

Having the book in my hands, and seeing it as something outside myself. I wasn’t sure I could ever do this. And now, of course, I’m going to do more...

Related articles:

- Ship Of Haunts by Ellie Stevenson [Book Review], Rennie's Book Blog, November 1, 2012

- Author interview: Ellie Stevenson, by Rachel Pictor, rachelpictor.co.uk, October 8, 2012

- 'Ship of Haunts: the other Titanic story,' by Ellie Stevenson [Book Review], by C L Davies, cldavies.com, September 28, 2012

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

[Interview_3] Gail McFarland

Gail McFarland writes contemporary romance.

Her novels include Doing Big Things (Lulu, 2012); Wayward Dreams (Genesis Press, 2008); and, Dream Keeper (Genesis Press, 2009). In addition to that, her romantic confessions and short stories have been featured in a number of magazines as well as in the anthologies, Bouquet (Pinnacle Books, 1998) and Can a Sistah Get Some Love? (Lady Leo Publishing, 2010).

Her work is available in both print and e-format.

In this interview, Gail McFarland talks about her experience of e-books, the future of the book and about her short stories:

How much of your work is available in print form and in e-format?

My novel-length work is currently available in print form and available for order and purchase in both online and brick-and-mortar-bookstores. In e-format, readers can find a dozen different stories everywhere from Amazon.com and B&N.com, to the ibookstore, Kobo, Diesel, Sony, and Smashwords.

Of the two formats, as a reader and then as a writer, which do you prefer?

This is a great question! As a reader who grew up pre-ebook, I absolutely love the feel of a book in my hands. I love experiencing the turning of the pages and the whole holding-my-breath as I wait to see what awaits me on the next page thing. But I am at heart a reader. Truth be told, I will read just about anything, so I am reading ebooks.

In my everyday real life, I work in Wellness and Fitness and for me, that is where e-books take the full advantage. They are easy to carry in my gym bag and I can read on the treadmill or while cranking out miles on a stationary bike. E-books are unmatched for downloading manuals and having ready reference available for my classes and clients.

I still love a real paper book, but I guess I’m just a woman of my times and a good e-book works for me.

In your view, what is the future of the book going to be like?

The ease of reading and the portability of e-readers is impressive. Additionally, the opening of the market to indie authors is allowing an unprecedented rise to free and open thought that was often lost among traditional publishers. This leads me to think that more people are reading – a good thing. It also leads me to think that more ideas are being more easily exchanged and that our society, as a whole, is expanding and reshaping itself accordingly – another good thing.

So ultimately, I think that both traditional and indie authors are going to have to step up our game to keep pace with this future, and that we owe this effort to our readers, ourselves, and the ongoing integrity of books.

You have an impressive number of your stories that have been published in a variety of anthologies. How did this happen?

One of the nicest things about writing for publication is that you are able to make contact with people whose hearts sing the same songs as your own. When that happens, how can you say, ‘no’?

I have been fortunate to find myself in the company of a number of lovely ladies for the Arabesque Bouquet Mother’s Day anthology, and the Lady Leo Can a Sistah Get Some Love anthology. Additionally, a number of my short confessions (27 of them!) appeared in collections for the Sterling/MacFadden Jive, Bronze Thrills, and Black Romance magazines.

In each case, I was invited to submit an idea and a subsequent story for the collection.

I was very happy and enjoyed doing it.

And here’s a little bit of a 'scoop' for you and your readers: I will be included in a new anthology featuring the GA Peach Authors in 2013. The anthology will include work from Jean Holloway, Marissa Monteilh (Pynk), Electa Rome-Parks, and me. As authors, we write across a wide variety of genres that include everything from erotica, murder, romance, and mainstream fiction, so this one promises to be big fun.

How have the stories been received?

Anthologies are nice little “samplers” of style and content. A reader may choose the book because they are partial to a particular writer or style, but in the reading, there are always little unexpected and surprising “jewels” to be found, giving the reader something fun and unexpected – a lot of bang for your reading buck!

I have been fortunate to be included in well-planned, well-thought out collections where the writers shared a similar vision and direction. This, combined with skilled editing results in entertaining, often dream-worthy collections of well-developed prose.

Each of the anthologies I have been involved with has generated a series of really nice reviews, lots of email, and even a few new fans of the individual writers.

All of the stories and their associated collections have been well-received, and readers often want to see fully-developed novels that will follow the characters forward.

Related books:

,,

Related articles:

Her novels include Doing Big Things (Lulu, 2012); Wayward Dreams (Genesis Press, 2008); and, Dream Keeper (Genesis Press, 2009). In addition to that, her romantic confessions and short stories have been featured in a number of magazines as well as in the anthologies, Bouquet (Pinnacle Books, 1998) and Can a Sistah Get Some Love? (Lady Leo Publishing, 2010).

Her work is available in both print and e-format.

In this interview, Gail McFarland talks about her experience of e-books, the future of the book and about her short stories:

How much of your work is available in print form and in e-format?

My novel-length work is currently available in print form and available for order and purchase in both online and brick-and-mortar-bookstores. In e-format, readers can find a dozen different stories everywhere from Amazon.com and B&N.com, to the ibookstore, Kobo, Diesel, Sony, and Smashwords.

Of the two formats, as a reader and then as a writer, which do you prefer?

This is a great question! As a reader who grew up pre-ebook, I absolutely love the feel of a book in my hands. I love experiencing the turning of the pages and the whole holding-my-breath as I wait to see what awaits me on the next page thing. But I am at heart a reader. Truth be told, I will read just about anything, so I am reading ebooks.

In my everyday real life, I work in Wellness and Fitness and for me, that is where e-books take the full advantage. They are easy to carry in my gym bag and I can read on the treadmill or while cranking out miles on a stationary bike. E-books are unmatched for downloading manuals and having ready reference available for my classes and clients.

I still love a real paper book, but I guess I’m just a woman of my times and a good e-book works for me.

In your view, what is the future of the book going to be like?

The ease of reading and the portability of e-readers is impressive. Additionally, the opening of the market to indie authors is allowing an unprecedented rise to free and open thought that was often lost among traditional publishers. This leads me to think that more people are reading – a good thing. It also leads me to think that more ideas are being more easily exchanged and that our society, as a whole, is expanding and reshaping itself accordingly – another good thing.

So ultimately, I think that both traditional and indie authors are going to have to step up our game to keep pace with this future, and that we owe this effort to our readers, ourselves, and the ongoing integrity of books.

You have an impressive number of your stories that have been published in a variety of anthologies. How did this happen?

One of the nicest things about writing for publication is that you are able to make contact with people whose hearts sing the same songs as your own. When that happens, how can you say, ‘no’?

I have been fortunate to find myself in the company of a number of lovely ladies for the Arabesque Bouquet Mother’s Day anthology, and the Lady Leo Can a Sistah Get Some Love anthology. Additionally, a number of my short confessions (27 of them!) appeared in collections for the Sterling/MacFadden Jive, Bronze Thrills, and Black Romance magazines.

In each case, I was invited to submit an idea and a subsequent story for the collection.

I was very happy and enjoyed doing it.

And here’s a little bit of a 'scoop' for you and your readers: I will be included in a new anthology featuring the GA Peach Authors in 2013. The anthology will include work from Jean Holloway, Marissa Monteilh (Pynk), Electa Rome-Parks, and me. As authors, we write across a wide variety of genres that include everything from erotica, murder, romance, and mainstream fiction, so this one promises to be big fun.

How have the stories been received?

Anthologies are nice little “samplers” of style and content. A reader may choose the book because they are partial to a particular writer or style, but in the reading, there are always little unexpected and surprising “jewels” to be found, giving the reader something fun and unexpected – a lot of bang for your reading buck!

I have been fortunate to be included in well-planned, well-thought out collections where the writers shared a similar vision and direction. This, combined with skilled editing results in entertaining, often dream-worthy collections of well-developed prose.

Each of the anthologies I have been involved with has generated a series of really nice reviews, lots of email, and even a few new fans of the individual writers.

All of the stories and their associated collections have been well-received, and readers often want to see fully-developed novels that will follow the characters forward.

Related books:

,,

Related articles:

- Gail McFarland [Interview], by LaShaunda Hoffman, Odinhouse Fantasy, July 14, 2012

- Gail McFarland [Interview_2], Conversations with Writers, April 5, 2010

- Gail McFarland [Interview_1], Conversations with Writers, June 2, 2008

Monday, January 14, 2013

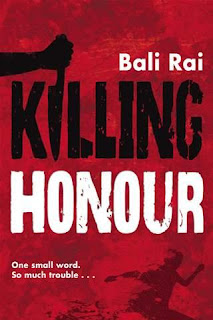

[Book Review] Killing Honour... a beautifully written, heartfelt book

Reviewed by Sarah O’Rourke, The Grassroutes Project*

Bali Rai is considered the writer of British Asian teen fiction, and it’s not hard to see why. Life bursts off the pages of his 2011 novel, Killing Honour. Rai tackles taboo subjects with incredible clarity and passion.

Killing Honour tells the story of Sat, a Leicester-born Asian teenager, whose sister is forced into a marriage with an abusive husband who then goes onto murder her – a so-called “honour killing.” Bai makes his stance clear on these killings in the title of the book and through the voice of his narrator, who never once gives up on his sister, no matter what izzat she has offended. Sat understands that family must come before honour, saying: “[A]ll you’re doing is killing it – killing honour – not defending it,” (KH p.180) but in order to unravel the mystery of his missing sister, Sat comes up against a “wall of silence” in the Sikh community. At the same time, of course, Sat represents those Sikh men who openly condemn such murders.

Killing Honour condemns domestic violence in any form, whether that be against Asian women or white women. By removing the “honour” from the phrase honour killings, Rai exposes these violent acts for what they are: murder without justification. Rai makes it clear how intolerable it can be for women who have to live up to unachievable standards to protect their family’s izzat. Sat notes that he is a male and so the “izzat thing” (KH p91) is easier for him, making his sympathy for women apparent, wishing that his sister had run away, because he could never have lived her life. Rai further instils a sense of sympathy for women by switching the point of view of his narration – sometimes it’s Sat, sometimes it’s third person from Laura’s perspective, and sometimes it’s the abused woman. Here we see the horror of domestic violence and murder from every perspective, from the family to the Asian wife to the abused white girlfriend. Rai considers all these people as victims of the same crime. Rather than privileging one over the other, he states emphatically that it is wrong. That it must be stopped.

Rai paints Leicestershire as a diaspora space – that is a community in which the consciousness of not only the first generation immigrants is transformed, but the indigenous peoples too, each changing and shaping one another together as one cohesive whole. Location figures heavily in Killing Honour, set in and around Leicester, with local landmarks such as De Montfort Hall, Victoria Park, Queens Road, and even Babella’s bar. Sat says that his sister “lived on the other side of Leicester, but it wasn’t far. Nothing in Leicester is.” (KH p.9) And this image of Leicester as a tightknit community can be felt not only in the novel, but in the city itself, with art reflecting reality and vice versa.

In Rai’s novel, Britishness figures as intrinsically culturally diverse. As Rai himself says, “we should celebrate what we have in common” rather than putting our differences first. And so we see Sat drinking from a Bart Simpson mug, the family visiting Disney World and hot dogs being eaten. When Sat gets a girlfriend who is white (a union frowned upon by people from both sides of the cultural divide), he is presented as very much the modern multiculturalist, showing the transformations that have taken place between first and second generations in the diaspora space of Leicester life. Sat says of his girlfriend: “Although we were both British, Charlotte came from one culture and I was from another. We were like the same, and then different too.” (KH, p38)